The Liberty Network on 3995 kHz, LSB

The Liberty Network on 3995 kHz, LSB

YouTube video made for Fred, KA2YLZ by Laura Fenik, N2JTT on February 15th, 2017: WNYS – Radio Ranch

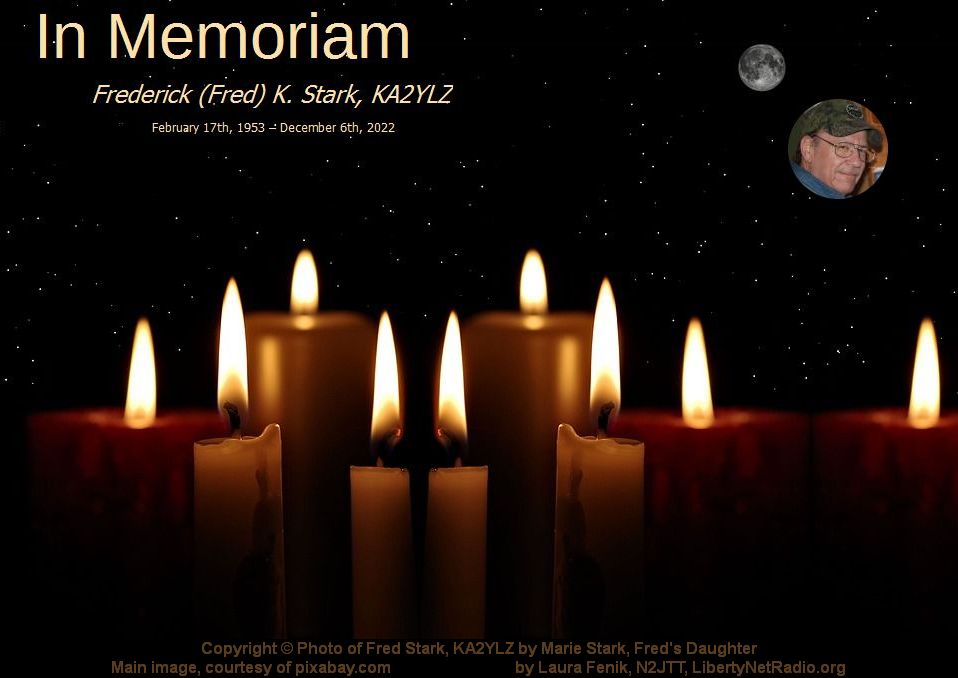

Frederick (Fred) K. Stark, KA2YLZ. February 17th, 1953 – December 6th, 2022. Columbia County, New York.

by Laura Fenik, N2JTT

February 17th, 2023, Fred would have been 70 years of age. His spiritual essence transcends the tangible.

Marie Stark (Fred’s daughter) denounces what has been written about her father on an opportunistic website which is run by Kevin Alfred Strom. Marie does not want her father to be remembered in the way that he is portayed on that web page. In Marie’s words: “Put something to discredit what that horrible Strom character wrote about my father.”

On multiple occasions, Fred broke bread with Marie’s husband Jimmy – a wonderful, intelligent Black man, who is an accomplished medical professional. Eden is their beautiful daughter. In my many talks with Fred, he would tell me of the friendships that he had with folks of Black and Jewish heritage. He was respectful to people of various ethnic backgrounds.

Fred was the utmost connoisseur and historian of specialized classical music. He could have been a college professor of music theory and music appreciation.

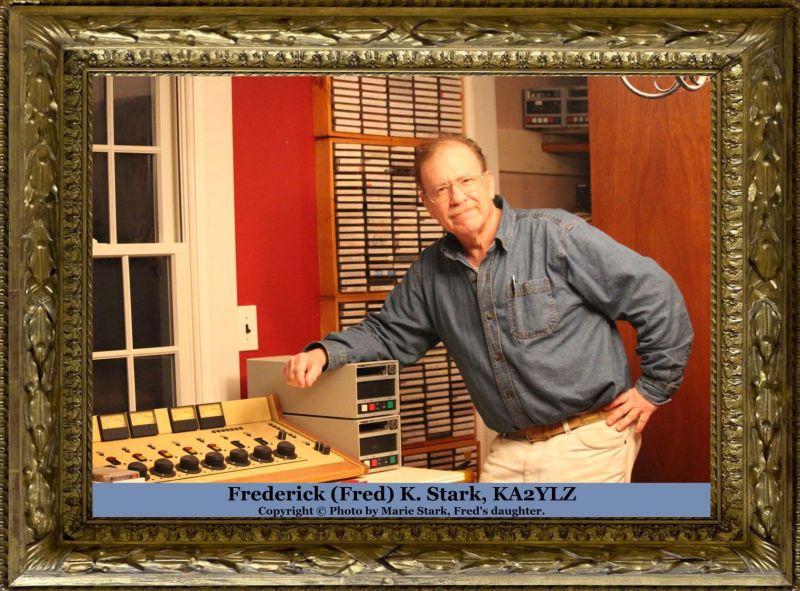

This man designed and built a remarkable radio station, WNYS at his home in West Taghkanic, New York. From there, he created and broadcasted programs of rare, lovely classical music.

See the two articles about Fred Stark, KA2YLZ and his radio station, WNYS further below: Christmas Eve, and the radio was stilled by Charles McCluskey, Hudson Valley Hornet, December 21, 1990 and The Last of WNYS’ “TOUCH OF CLASS” by Don Bishop, Monitoring Times, May 1990.

Stark’s Music From the Podium was an endearing feature of the Liberty Net. In this forum, Fred selected a wide array of ear–pleasing, magnificent, and succulent classical music.

Fred’s sonorous voice, warm personality, and infectious laugh will be deeply missed by many.

You are an irreplaceable gem, Fred. R.I.P.

Commentary by Marty Fenik, N2IRJ

Being a preservationist of history, I believe that all possible details should be documented. Therefore I will provide additional information that the two below articles about Fred do not. My source was Fred Stark himself.

First, the “unnamed entity” that put the nail in Fred Stark’s coffin was allegedly one Richard Novak. It appears that his motivation was based upon envy, pursuit of grandeur, and unmitigated hate.

Another tidbit is that the FCC agent visiting Stark’s home was driving an undercover Buick.

Fred Stark lived by what he called the “100–100 rule.” This means that low power broadcast stations such as his, on a clear channel, would have peak power limited to 100 watts and the antenna length would be no greater than 100 feet. The reason for such self–imposed restrictions was to ensure that the listening audience would remain local and that he would never cause interference to any distant station. These technical handicaps were quite severe for his broadcasts on 1000 kHz but became extraordinarily severe when he operated around 640 kHz. Fred’s first and foremost philosophy was to never lessen anyone’s pleasure and to ensure good engineering practice.

As for his power output restriction, he utilized two 6146 tubes in the RF final. This configuration was similar to what was utilized in a Yaesu Musen FT–101B Amateur Radio. Fred was so proud of his design and tube compliment that he even incorporated a hint of that into his email address which was: RadioGuy6146@AOL.com.

Lastly, the overly harsh FCC fine of $1000.00 was reduced to under $500.00. This was because Fred’s tenaciously loyal wife Leonor met at FCC headquarters and successfully plead a case for lowering the fine.

In closing, Fred Stark gave birth to classical beauty over the airwaves –– commencing in December 1967. The chance of this ever happening again terminated upon his death in yet another December –– 2022.

One final morsel of agony: Enver, Fred’s beloved meowing cat on Liberty Nets also died in response to an interrupted feeding schedule along with emotional heartbreak.

Ouroboros.

We are saddened that it is over but we rejoice for the cycle of life which allowed this miracle to have happened.

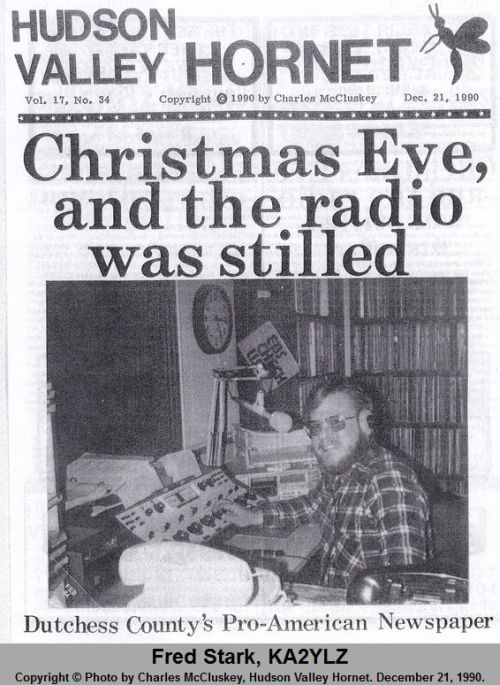

(This article, written by Charles McCluskey, originally appeared in the December 21st, 1990 issue of the Hudson Valley Hornet and is reproduced here with permission from Charles McCluskey, founder, owner, and publisher of the Hudson Valley Hornet.)

Stave One

What Fred Stark was doing was illegal to begin with. Unless it is clearly understood that Fred Stark was operating outside the law, then nothing wonderful can be expected to come of this tale.

Fred Stark’s dream has been as dead as a doornail since December 17, 1989. Mind you, I only say “dead as a doornail” because that’s the way Charles Dickens put it. And, though our distribution is still a bit late in this imperfect world, this is still a Christmas tale worth telling.

It is a melancholy tale fitting for the lag days after the holiday, and especially for those who are a bit “down” for failing to grasp the real meaning of the Christmas season.

Fred Stark, born Frederick K. Stark, is a radio technician, a man of almost furious enthusiasm. We first met him about a decade ago when he came to pick up some back issues of the Hornet to distribute among his friends in Columbia County.

It has been observed that the problem with young people is that they believe everything that people tell them. If that’s so, then the problem with those of us whose beards are gray is that we tend to believe nobody. And the results can be sad.

Years ago, Fred Stark invited us to come and visit his “pirate” radio station. Fred operated, with what we came to think was colossal nerve, a regularly–scheduled, completely illegal, AM radio station––and he did it from his home in Columbia County, every Sunday at the same time, year in and year out. As many readers will know, the Editor spent many years in radio. We just couldn’t believe that it might be possible to operate an illegal radio station between New York and Albany, right there in broad daylight, with station breaks, call letters, and everything any other regular radio station had––except a license to do it. Perhaps we can be forgiven for failing to believe something when it seemed impossible on its face. Although we never met an FCC representative in all our years of broadcasting, we knew they were there. A former employee was, in fact, ordered by the FCC to sell or shut down within 90 days because his program director was caught tampering with the political advertising of someone on his enemies list. The FCC will get you if you don’t behave.

How then did Fred Stark operate an illegal radio station in southern Columbia County not for six weeks, six months, or even six years, but for fully 22 years, Sunday in and Sunday out? Well, it may be that nobody complained until the very end.

It puts us in mind of some city people who moved to a little town in New Hampshire, and the following month, before they had all the boxes unpacked, brought a suit against the local board to silence a church bell that chimed the hour and the quarters thereof night and day. Things being what they are today, of course, they won their lawsuit. And the little New Hampshire village, a very little village, had to do some scraping to meet the legal fees and to buy a $350 timer to turn off the bell at night. Welcome, stranger, hope you like our town…

Fred’s kind of a conservative, and he believes that a newcomer to his area, a liberal who nowadays operates a radio station in Poughkeepsie, was the one who flipped him in to the Commission. Now, mind, the rat–fink who informed had every right and obligation as a citizen to do so. Fred, as we said, was breaking the law.

Stave Two

Fred Stark was not your average pirate–radio operator. He deplored the filth that pirates in urban areas love to dump out in the dark of night on the airways. Fred was out to create a quality sound. And, according to Monitoring Times, a broadcast magazine, he was rewarded in a way. It is believed that Fred may hold the all–time duration record for operating an illegal radio station.

As a boy, Fred was a faithful listner of WHAZ, a thousand watter located at 1330 on the AM dial. (Not a particularly great frequency for getting your signal out a country mile, but better than some.) There are, for instance, more radio stations at 1450 on the AM dial than at any other frequency. If they get out more than seven miles in any direction, everyone’s happy. WHAZ was operated by Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.You have to assume that if nothing else, the technical quality must have been superb with all those engineers on the premises.

Fred learned to love classical music from listening to WHAZ. Fred learned to love radio in a way that was once a tremendously popular hobby in America, particularly in the 1920s: listening for distant stations. He once heard an AM station at 891 on the dial in Algeria, and as a youth picked up KSL in Salt Lake City. Fred says that distance–listeners––DX–ers, they’re called, once picked up KFI, Los Angeles, in Columbia County. He was never able to duplicate that.

It costs a lot of money to put a radio station on the air. We knew a man from Rockland County who spent fifteen years and all the money he could lay hold of, working two full–time jobs, trying to get an AM license. Finally, he had to settle for a relatively small share in a partnership basis. He died young.

In the Hudson Valley, you can sell an FM station with virtually no listeners for half a million dollars. If the FCC approves you, all you have to do is put up enough cash to operate a full year with no income whatever. That’s because there are too many radio stations, and your income very well may be none whatsoever.

Fred knew he could never afford to put a legal radio station on the air. As a technician, with a working knowledge of how the business operates, and how the FCC works––like many government agencies, it is somewhat understaffed, particularly as concerns field investigators. The government’s teeth may be sharp, but they are also few and spaced out.

Fred decided it was worth the risk to put an illegal station on the air. The fact that he decided to broadcast on Sundays only, and during daylight hours, probably contributed to the station’s longevity. It would suggest itself that people are less given to complaining (or doing anything else) on Sunday than on any other day. And radio stations don’t interfere with each other nearly as much in the daytime as they do at night, when AM radio waves bounce higher in the sky, off what is called the Heaviside Layer, after Oliver Heaviside, the man who discovered it.

All other things being or seeming equal, it is most likely that anybody who happened to tune in to Fred Stark’s station assumed that it had every right and reason to be there. We’ve never seen WQXR’s license or its Public File; neither have we ever doubted for so much as a second that WQXR has a license. Some things you just assume are in order.

Stave Three

Fred’s broadcast day began at 9:00 a.m. Sunday over his 75–watt station, WNYS, located at the 1,000 spot on the AM dial. First program up was called “Morning Hangover Symphony”, with Your Host, Alex Hazeltine. At noon, “Air Magazine,” hosted by William Mathias, took up its weekly role. Fred, of course, was both Alex Hazeltine and William Mathias. Such reasonable–sounding, genuine, sound–as–a–dollar names! The noon program featured rebroadcasts of programs that originally were aired during what has been called “the golden age of radio.” At 2:00 p.m., William Mathias came back to the mike with “Afternoon Concert.”

The station signed off at 5:00 p.m. Every Sunday. For 22 years!

According to our Daybook entry for December 16, 1989, this area received five inches of snow. Fred lives in West Taghkanic, and we surmise that his area must have gotten at least as much. So, whether cloudy or bright, Sunday, December 27, 1989, was without doubt wintry in appearance, probably cold and windy in West Taghkanic. Christmas–y. Lights on the houses. Everyone anticipating the coming holiday.

The following Sunday, December 24, was, of course, Christmas Eve. Fred told us some weeks back that he had picked some special music to entertain his audience. (Again, getting into the realm of surmise, we’d make a guess that he probably had about 100 regular listeners, which is more than a couple of legally–licensed Dutchess County stations had during some recent rating periods!)

The knock at the front door had to come sooner or later. It came at 2:00 p.m. on December 17th. The man doing the knocking was one Judah Mansbach, an FCC electronics engineer with the credentials to prove it. Fred, of course, invited him in.

Mr. Mansbach took notes, looked at the equipment, and informed Fred that what he was doing was illegal. Fred did not contest that. As Fred told Monitoring Times, “It was December 17, so we were playing some Christmas music, Good King Wenceslas by Percy Faith. That side of the album ended and we faded down and there was dead air for five minutes while he checked everything over. That was the last thing we had on the air.”

Eventually, Fred was ordered to pay a nominal fine. It has to be said that the FCC was rather decent about the whole thing. What Fred Stark had done was illegal, of course, but in remarkable contrast to so much of the irredeemable swill that spews out on radio, TV and cable, what Fred Stark did was never offensive.

Like as not, at nine o’clock in the morning, on Sunday, December 24, 1989, about the time Santa was preparing to harness up his famous reindeer, somebody up there in Columbia County, and perhaps as many as two or three dozen good citizens, turned their radio dials to 1000 on the AM dial. And there was nothing there but “hash” from distant stations.

It was Christmas Eve, and the radio was stilled.

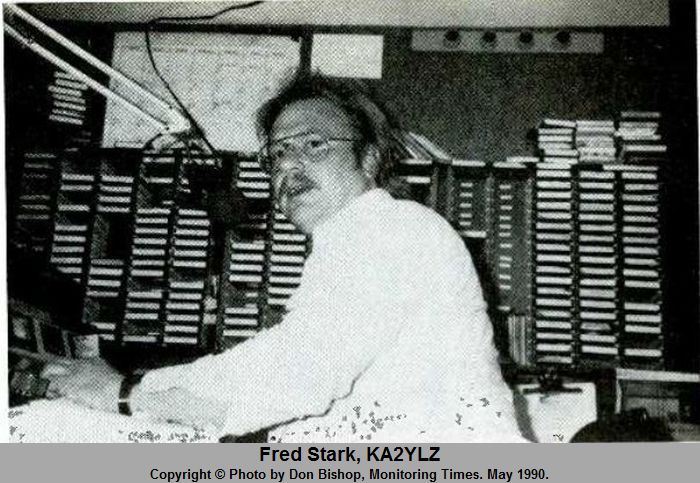

(This article, written by Don Bishop, originally appeared in the May 1990 issue of Monitoring Times magazine and is reproduced here with permission from Robert B. Grove, W8JHD, founder and publisher of Monitoring Times and Ken Reitz, KS4ZR, former managing editor, features editor, columnist, and feature writer for Monitoring Times; editor and publisher of The Spectrum Monitor.)

The United States’ oldest mediumwave pirate ends 22 years of weekly broadcasts and fades to dead air on December 17, 1989.

Frederick K. Stark’s time tunnel sucked in radio airwaves from the 1960s and breathed them out into the light of New York’s Hudson Valley. Every Sunday afternoon for the past 22 years, Frederick Stark has recreated a classical music program from the 1960s on his radio station. Every Sunday for the past 22 years, Stark faithfully recreated a radio program that he listened to as a youngster drawn to classical music. That program, also broadcast on Sundays, was transmitted over the 1,000 watt facilities of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute’s 1330 kHz WHAZ.

Music and Radio

“I listened to WHAZ when I was small,” said Stark. “I learned a lot of classical music from that station.”

I wanted to be a conductor and composer. I wanted to make records for the young person like myself who rarely gets to go to concerts. I wouldn’t look for big publicity, just to be a recording artist who presents classics to shut–ins and people who take time to listen, ” said Stark.

“I play the violin. We even have a piano in the house. I compose some music. I wrote a serenade for string. Someday I’ll write a symphony. It takes me a long time, the mechanics of getting it down. But I do have the ideas, and I pick up a melody like that. I wanted to be a composer –– conductor –– and then the radio bug hit me.”

WNYS Sunday program schedule:

9 am –– “Morning Hangover Symphony” Host: Alex Hazeltine

Noon –– “Air Magazine” Host: William Mathias

Rebroadcasts of programs originally aired during “the golden age” of radio.

2 pm –– “Afternoon Air” Host: William Mathias

5 pm –– Sign–off

DXing

Radio gripped Stark by the ears and pulled him into DXing, a hobby in which listeners strive to hear stations as far away and in as many locations as possible. “I was nine or ten years old when I got a shortwave receiver, the Star Roamer by Knight–kit. It was only half–built when I turned it on. The first station I picked up was Radio Berlin International. I was so hungry for shortwave.”

Stark soon found he got more pleasure out of DXing the AM band than the shortwave frequencies. With careful listening on 891 kHz, he heard an Algerian station, “the most distant station I’ve heard. But what I’m trying to pick up is California. Years ago, people tell me, KFI, Los Angeles, was received here. I always wanted to pick up the west coast. The most distant station I ever picked up as a preteenager was KSL, Salt Lake City.”

But listening wasn’t the only thing on Stark’s mind. “ I’ve always wanted to own a licensed station. But it is basically impossible to go through proper channels to obtain a license. It takes big bucks –– megabucks –– to start a station.”

Dream Channels

Over the years, Stark’s dreams were channeled into other achievements. Instead of becoming a composer–conductor, he learned to play instruments and amassed a huge library of classical music. He studied electronics, became a two–way radio technician, earned commercial and amateur radio operator licenses, and built WNYS, where his dreams were realized eight hours every Sunday.

“Urania” Brand

Stark began to build his own equipment, first a console, an audio processor and then line amplifiers. “All the equipment was designed and built in–house, except the reel–to–reel and cartridge tape machines and the turntables. ‘Urania’ was to have been my brand name, the top–shelf name in broadcast equipment. A lot of today’s transmitters are not designed by audiophiles. The WNYS equipment was set up by an audiophile –– me.”

First operating from his parent’s house, Stark used his transmitter and studio equipment as a pirate broadcaster. His call letters and frequencies changed over the years to avoid using letters assigned by the FCC to someone else and to dodge interference. What once was WNYW on 650 kHz and 640 kHz became WNYS on 1000 kHz.

During his service in the army, Stark was stationed at a base nearby. He came home almost every weekend to broadcast. He did the same while attending college.

After he married, Stark and his wife bought the house across the street from his parents’ house, and WNYS moved in with them. When a new station forced WNYS off 640 kHz, Stark relied on his AM DXing experience to pick 1000 kHz. “I know the AM band allocations like the back of my hand. I know where to broadcast so as to not interfere with another station. The 1000 kHz dial position is clear during the day. At night –– WNYS never was on at night –– WLUP, Chicago, broadcasts on that frequency.”

Stark said a “top hat” antenna boosted the station’s coverage. “The ‘top hat’ part of the antenna is four horizontal wires suspended between two towers, ” he explained. The wires connect in the center to a vertical wire that drops to an antenna tuning unit at ground level. Copper cables and rods buried beneath the earth under the antenna form a ground system. “I always say you never have enough ground.” “WHAZ,” Stark said, “had a top hat antenna during its early years.”

WHAZ “Returns”

“I longed to bring back the times of WHAZ,” Stark said. His homemade studio and massive classical music library recreated WHAZ’s Air Magazine and Afternoon Concert programs. His 75–watt transmitter broadcast as WNYS at 1000 kHz on the AM dial –– broadcasts that continued for the next 22 years. “One of our mottos was ‘WNYS, a touch of class in the Hudson Valley, West Taghkonic, New York.’”

Sunday Morning Hangover Symphony filled the 9 a.m. to noon period. It was “the perfect program to help one recover from Saturday night, if it’s been one of those nights.” Symphony was not patterned after WHAZ; the Troy station had no broadcast during that period.

“The afternoon shift at my station was exactly the same as WHAZ’s, ” Stark explained, “including the music.” Air Magazine included rebroadcasts of programs from “the golden age” of radio.

“Some of the listeners collected old radios,” Stark said. “They would fire up their old radios and hear shows like Fibber McGee and Molly and Amos and Andy on their Atwater Kent and Crosley receivers. They were overjoyed when I carried the old radio shows.”

Fred Stark, a radio amateur and two–way radio service technician, set the record as the longest–running medium wave pirate broadcaster in the United States.

Air Magazine’s introductory theme music was Typewriter by Leroy Anderson, performed by Arthur Fiedler and the Boston Pops. The program closed with a short instrumental theme.

At 2 p.m., Stark, as William Mathias, hosted the Afternoon Concert program of classical music. “No pretty-boy performances, such as Zuben Mehta and Leonard Slatkin,” he said.

Afternoon Concert shifted its emphasis at 4 p.m. with a pops concert, including collectors’ items on the Epic label and recordings by Arthur Fiedler and the Boston Pops. One more echo from WHAZ at three minutes to five, as Stark played as the closing theme the second movement of Mahler’s first symphony, the same closing theme that WHAZ used in the 1960s. The sign–off played at 5 p.m. and WNYS left the air at 5:05.

WYNS avoided detection by the FCC for a remarkably long time. Said Joe Reilly, president of the New York State Broadcasters Association, “This has been going on for ten years. This guy is a legend in that area of the state.”

Stark came to Reilly’s attention when a radio listener blew the whistle on WNYS, asking Reilly to tell the FCC. “A listener wrote a letter describing the pirate station as a nuisance. He asked what could be done about it.”

Reilly called Kevin McKeon, a friend of his at the FCC’s New York office. McKeon, a public affairs specialist, told Reilly to see if he could get a tape recording of a WNYS broadcast. “I told the listener what McKeon said, and the listener recorded WNYS. The listener sent me the tape and I sent it to the FCC. McKeon called back and said, ‘You got one. Where does your listener friend say the pirate station is?’ Then the FCC sent a mobile unit to go out and get the guy.”

Who Blew the Whistle?

The listener wants his identity kept secret. Regulatory agency administrative actions differ from judicial proceedings in that complainants’ identities are not revealed if they request privacy. But few listeners know state broadcasting associations exist. Stark believes the complainant represents a broadcast station licensee who became annoyed with WNYS –– and maybe jealous of its classical programming. Pirates have pride:

“We had the finest fidelity on the air possible for an AM station. Our distortion was extremely low. You didn’t hear any. We had a wide band of audio. The highs sounded like FM. We had the deepest bass, the highest highs – a very clean tube–like sound, which makes sense because everything was tubes,” Stark boasted. “A listener called up and told me about another station some distance away playing classical music. ‘How do you know you’re tuned to our station?’ I asked. ‘Because yours sounds better,’ he answered. Our fidelity speaks for itself. That was one thing we had to offer. You normally don’t hear much talk about fidelity on AM.”

WYNS Equipment:

Urania 100–watt transmitter

Urania control console

RCA cart machines

Urania audio processor

Technics turntable

Russco turntable

2 Ampex reel–to–reel tape recorders

Clinging to 1000 kHz

The “other classical station” is WKZE, 1020 kHz, a station that broadcasts classical music for an hour or two on Sundays. It began broadcasting October 27, 1986, with 250 watts and upped its power to 2,500 watts in March 1989. Stark’s failure to give WKZE more clearance by moving WNYS to another frequency may have led to his downfall.

Sometime after WKZE boosted its power, a deficiency in its studio–to–transmitter link developed. The STL receiver did not filter the 19 kHz stereo pilot signal, instead passing it to the AM transmitter. Modulated by the 19 kHz pilot, WKZE’s transmitter emitted spurious signals at 1001 kHz and 1039 kHz, 19 kHz to either side of its 1020 kHz carrier frequency. The spurious signal at 1001 kHz interfered with WNYS.

“When I was off the air during the week, I would listen in the early morning to WLUP on 1000 kHz,” Stark said. “WKZE would go on the air about 6:45 a.m. to 7 a.m.. As soon as they threw their carrier on, the tone would come right in.”

He thinks one or more WNYS listeners may have figured out the problem and complained to WKZE. Those complaints, he believes, may have led to a WKZE complaint against WNYS. But WKZE General Manager Drew Wilder said he heard about WNYS only after it was closed down. The station’s contract chief engineer, Dave Groth, said he did not complain to the broadcaster’s association or anyone else about Stark. Groth confirmed the stereo pilot signal problem, which he repaired by installing extra filters on the STL receiver.

“I didn’t realize WKZE was broadcasting spurious signals until I got an anonymous call saying there was a beat frequency between WKZE and this other station that went off when they went off the air,” Groth said. “That’s when I located the pirate. Actually he was playing good music, classical, which is unusual. I do not condone anything illegal. But it is refreshing to hear a classical format on AM. It is illegal, but it is an alternative program. Pirates often have programs that legal stations cannot or will not play.”

Groth said if a pirate station’s broadcast ever would interfere with any of his client stations’ signals, he would take action. “We had listeners saying there were beat frequencies,” he said, but the beat frequencies affected WNYS, not WKZE. “The New York FCC did pay Stark a visit. I had made no calls. I had not taken any action. It is possible the FCC, monitoring the bands, found WNYS themselves.”

Fred Stark: “WNYS, a touch of class in the Hudson Valley, West Taghkonic, New York.”

“Sunday will never be the same. WNYS was my whole life.”

Groth and Stark are acquainted with one another because Groth keeps the keys to a radio communications repeater site that Stark sometimes visits as part of his job as a two–way radio service technician. But Groth said he did not know Stark was the operator of WNYS until the bust made local news.

“Is there more to the listener’s complaint than meets the eye?” broadcast association president Joe Reilly asked. “I don’t know. The listener may not have agreed with the programming Stark was putting on. I just got the letter and did what I normally do. The association has a working relationship with the FCC. We interface with the broadcasters on some issues. When the FCC gets a complaint against a broadcaster, sometimes the agency asks us to call the broadcaster. We’ve been able to defuse a lot of situations with that relationship. Stations get defensive when the FCC calls.”

When WNYS was on the air, “the listener claimed he couldn’t get his regular radio station,” Reilly said. “The interference was intermittent. I don’t know why he didn’t write the FCC. I’ve had other calls about pirates. But this is the first the association has ever taken action on. I’ve had calls but listeners generally don’t follow through. In this case, the letter was well written and the listener followed through.”

Interference to 1010 kHz

An FCC press release cited interference WNYS caused to “a licensed station on 1010 kHz.” The nearest such station is WINS, a 50,000–watt station in New York. According to Stark: “Number one, you can’t hear WINS in this part of the state. Number two, even nearer to New York City, WINS does not come in well, because of its directional antenna. In Poughkeepsie, where I work, WINS does not come in well. Number three, if you’re down the road and you’re trying to listen to 1010 kHz, you’re going to get some splatter.”

So what. None of this matters to an FCC engineer, who will close a pirate station whether it causes interference or not.

The Day of Reckoning

Thus, on December 17, 1989, at about 2 p.m., FCC electronics engineer Judah Mansbach traced the WNYS signal to Stark’s house. “The doorbell rang,” Stark said. “I thought to myself, ‘It must be Jehovah’s Witnesses or somebody. I’ll go outside and chase them away.”

It was Mansbach ringing the bell at the front door. “I usually don’t use the front door,” Stark said. “‘Come over to the side door,’ I told him.” He did.

“‘Hello, I’ve been listening to your station,’ he said.”

“‘Oh, and who are you?’ I asked.”

“‘I’m the FCC,’ he said.”

“‘Do you have ID?’ I asked. You always ask for ID when the FCC comes,” Stark advised.

“He showed ID and asked, ‘May I come in?’”

“Being as I’m easygoing, I invited him in. He came in, saw the setup, took notes and that was that. He said that it was wrong, that I was a pirate radio station and it is against the law to do this. Then we went downstairs and looked the transmitter over.

“It was December 17, so we were playing some Christmas music, Good King Wenceslas by Percy Faith. That side of the album ended and we faded down and there was dead air for five minutes while he checked everything over. That was the last thing we had on the air.

“It’s a shame, because I had a nice Christmas program planned for the day before Christmas, which was the Sunday of the following weekend.”

Stark said he asked Mansbach whether he wanted to take the transmitter; Mansbach said no. “He asked me what other licenses I had; I told him about my commercial and amateur licenses.” Stark said Mansbach told him the FCC would get in touch with him in a few weeks. “They sent me a letter and fined me $1,000. A warning would have been fine. I guess that is the cost of broadcasting.”

Stark seemed a little miffed that Mansbach used his direction–finding apparatus to locate WNYS. “All you had to do [to find us] was go to the post office. We gave our address on the air quite a bit for requests and comments. A regular listener would know the address by heart.”

Mansbach was not as impressed with Stark’s station as Stark himself is. “I found a homebrew transmitter and an army surplus power supply, ” the FCC engineer said, “and the usual stuff for audio. It wasn’t a great station. He wasn’t really trying to push it.” Why didn’t Mansbach accept Stark’s offer of the transmitter? “It was built out of breadboard. He said he would destroy it and I believed him.”

Stark confirmed: “I told the FCC I would get rid of the transmitter. My fear was if they were to come by again and see the thing back up. I’m already in the frying pan. I didn’t want a fatal hotfoot. I undid everything.”

Mansbach did not see the WNYS top hat antenna, which had been destroyed not long before by a windstorm. “Stark had a dipole cut to size and hidden in a tree,” Mansbach said. Asked whether he meant a halfwave dipole, which for 1000 kHz would be approximately 500 feet long, Mansbach said he did not know. “Stark is a radio amateur; he knew what he was doing when he built the antenna,” he said.

The Lone Pirate

Mansbach said most pirates are part of a group, but that as a pirate, Stark was a loner and unusual in that respect. Stark has few compliments for other pirates: “Most pirate stations deserve to be caught. The profanity. I picked up some stations years ago, on 1610 kHz or 1620 kHz, from New York City. They sounded horrible. They sounded like their audio response was from 300 kHz to 3,000 kHz. They had 60 Hz hum. Their modulation was distorted. The profanity and garbage they played. They deserve to be taken off the air.” No mutual admiration from Stark.

The former pirate operator said he would never have used shortwave. “When you’re on shortwave, you’re going worldwide. My audience is local. In a car you don’t have a shortwave radio. Cars have AM radios. My target is the local community.”

FM was out, too. “I didn’t go FM because in the 60s AM was more popular. Where I live, we’re in a hole, the bowels of Columbia County.”

Stark said WNYS was “like a novelty. It primarily was for the promotion of classical music. We had 50 to 100 listeners, based on mail received. We are missed in the area and many people felt it filled a vital need. After we went off the air, the phone rang off the hook. ‘Sorry to see you go,’ ‘My Sundays are ruined,’ and ‘What am I going to do now,’ people said. A lot of people depended on the station.

A Hobby that Grew

“WNYS started as a hobby, a young kid setting up station and running it. Later on, the station grew into something good. It had a lot of listener response. We did fill a need in the community. We are certainly missed. Many are missing us already,” Stark said.

H.V. Henninger is a classical music fan and mediumwave DXer in Saugerties, New York, 17 miles from WNYS. He had been a regular listener since about 1984, when he first noticed the station. Not long after he first heard WNYS, he sent a reception report to the address Stark announced frequently. Confirmation came in the form of a personal visit.

“I had a knock on the door,” Henninger said, “and Fred introduced himself and came in. We had coffee, then went upstairs to the radio room and I played back the tape of his station. That’s how I got to know Fred.”

Henninger was a frequent listener who followed the station’s transition from 650 kHz to 640 kHz and finally 1000 kHz. “I rarely ever missed a broadcast,” he said. “I’m off work Sundays so I always listened to him. We would talk frequently, and over the years his broadcast quality got better and better. He was always tweaking and adjusting the Urania transmitter.”

In Saugerties, Henninger heard the heterodyne caused by WKZE’s malfunctioning STL receiver. He heard it when he drove as far as 70 miles away from WKZE, where it beat against another station’s carrier. Now the heterodyne is gone, and so is WNYS.

“That station essentially made my day on Sunday,” Henninger said. “I listen to a lot of classical music, which is something Fred and I have in common. He has the kind of record collection that, to a person who enjoys good high–quality classical music, cannot be beat. That station was his life, really. He worked at that station; that was what he spent the majority of his free time on. He would go to various record stores looking for new material to play.”

Henninger said Stark’s mother always was afraid he was going to get caught. “His wife was not that keen on it, either. She was afraid he was going to get caught some day. But she understood this was his life, that he had been on the air 22 years. He is the longest–running mediumwave pirate in the United States.”

A Typical WNYS Music Log:

9 a.m. “Sunday Morning Hangover Symphony”

Beethoven: Twelve Contra Dances

Moniuszko: “The Raftsman” overture

Draeseke: Symphony No. 3

Saint–Saens: Piano Concerto No. 4

Andreyeu: “Under the Apple Tree”

Grieg: Symphony

2 p.m. “Afternoon Concert”

Saint–Saens: Symphony No. 3 (Organ Symphony)

Shumann: Symphony No. 1 (Spring Symphony)

Beethoven: String Quartet No. 2, Op. 18

Bartok: Concerto for Orchestra

Tchaikovsky: Swan Lake Ballet–excerpts

QSL Cards

Stark said even though WNYS is off the air, he will verify correct reception reports. The station occasionally made evening equipment tests that may have been heard beyond the local area, he explained. Reports can be sent to: WNYS, Rd 1, Box 191, Elizaville, NY 12523.

“The next time I broadcast, it will be with a license,” said Stark. He might put the station on cable, an idea that occurs to many pirates after they are busted. “We don’t have a cable company in the area. Maybe I’ll turn the red light on and beg for money to put together a cable system. I can go cable FM and supply TV for viewers, too. I’d put together a small studio once again and have fine programming.”

Stark said he talked with the FCC about the future possibility of obtaining a broadcast license. “They said my WNYS operation wouldn’t affect my eligibility. I would like to have a licensed station. But it is hard to get the money and meet the criteria. For the common Joe who goes to work, it is an impossible dream. I ran WNYS as if it had a license. Everything was done to the book.”

Actually, Stark broadcast one more time, as a guest on WPYX–FM, 106.5 MHz, Albany, New York. The station’s morning DJs, Bob Mason and Bill Sheehan, read a newspaper story about Stark on the air when Stark and his coworkers at New York Communications’ radio service shop in Poughkeepsie were listening. “The guys in the shop said, ‘Hey, Fred!’”

The DJs called Stark’s parents, who gave them the shop number. Stark took a vacation day to be heard on their show. For his musical introduction, Stark brought the overture to Gilbert and Sullivan’s Pirates of Penzance, which faded in with Hail, Hail, the Gang’s All Here and was followed by Bobby Fuller’s I Fought the Law and the Law Won.

Now, Stark’s pirate broadcasting days are over. But radio continues as part of his life. He services police, fire, business and industrial two–way radio equipment at New York Communications in Poughkeepsie. Radio signals emanating from his West Taghkonic home are confined to the amateur bands where he is heard communicating as amateur station KA2YLZ. Classical music continues to play, but only in the Stark’s living room. The Hudson Valley has lost “a touch of class.”